The Separation Files, part 1: The Cowherd and the Weaver Girl

What would we do for love?

If I go to the heavens in search of the divine, will I like what I find? Is it worth the risk?

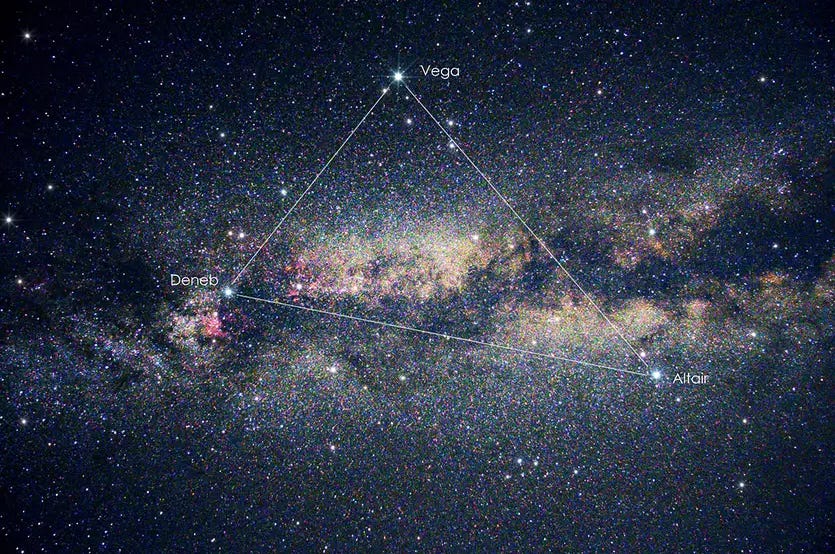

I recently found myself high on a hill in the Wisconsin countryside, listening to the crickets chirp and watching the stars come out as the dusk faded to night. On warm summer nights like this, when twilight lingers long and the earth breaths out the day’s heat, I first look for the three bright stars of the summer triangle, a huge isosceles triad covering nearly a 5th of the visible sky, with, on dark nights, the Milky Way visible flowing directly through its heart.

Almost always my eyes are first drawn to Vega, the brightest of star in this part of the sky. It floats majestically above the Milky Way as it rises, trailing a trapezoid of faint stars, a fitting entourage beneath it.

I then might scan along the long isosceles axis to the also brilliant star Altair. Second brightest and furthest from Vega, Altair sits beneath the Milky Way, flanked by a fainter companion star on either side.

Finally I complete the triangle with the star Deneb, which, with the other bright stars of the constellation Cygnus, the Swan, swims among the faint fuzz of the Milky Way.

High in the sky, these three stars crown midsummer nights, brilliant adorning jewels visible even from the light polluted confines of my Chicago home. Sometimes, when the sky is crystal clear, they feel close, as if bending near so that if I just stretched my uplifted fingers just a little further I might touch their burning light. Yet most days they seem more distant - though I crane my neck they seem no closer, though I brandish my telescope, they remain, through its lenses, just distant points of light.

I know, of course, that parallax measurements place Vega at a distance of 25 light years - 150 trillion miles - a trip of some 5000 lifetimes with current space technology. And Deneb some 100 times farther. But though I can crunch the numbers, I still am not sure I fully understand. I still am left wondering: how high, really, are the heavens above the earth?

Perhaps what I really want to know is: how far must I travel that I might encounter the divine?

There’s an ancient Chinese folktale that prominently features these three summer triangle stars. Though it’s a tale that takes many forms, and though I'm sure much has been lost in the great chasms of cultural translation, it’s a story that somehow still speaks to me. Let me tell you the version I know.

Zhi Nü was the seventh daughter of the Jade Emperor, the ruler of the heavens. Renowned for her beauty and skill, she could weave the most beautiful cloud tapestries, sewing stunning garments for the heavens, her fingers a blur of rainbows and dancing sunbeams.

But for all her skill, Zhi Nü’s responsibilities as the heavenly weaver felt to her as an isolating cage. She longed to experience the earth she so beautifully dressed, to connect with its inhabitants and break the monotony of her life. Though the Jade Emperor forbade most interactions with mortals, her sisters agreed to accompany her on a secret trip to a remote place on earth, where they might experience its beauty undisturbed. They donned robes that allowed their decent and travelled to earth. Zhi Nü found it a magical space, even more wonderful than she imagined; as she swam in the clear mountain lake she dreamed of a life here, of this moment continuing on and on.

Eventually her sisters slowly tired of their splashing, and one by one flew back to the sky. But Zhi Nü continued to swim and float in the lake, soaking it all in. Secretly she was glad her sisters had left, glad for the freedom of this moment alone.

But unbeknownst to Zhi Nü, she was not alone.

For, you see, nearby there lived a lonely cowherd named Niu Lang. Orphaned at a young age and forced to live with his cruel brother and sister-in-law, Niu Lang had only a small plot of land and an old ox with which to make a living and survive. With no other companions to talk to, Niu Lang would tell his troubles to the ox as they worked his infertile land, and their bond was such he was sure the ox would understand.

One day, to his surprise, the ox spoke to Niu Lang, revealing that he was a fallen deity who would soon die, but who would leave Niu Lang the gift of his hide, which would allow him to travel to the heavens to seek his heart’s content. The ox also told Niu Lang of the divine maidens descending from the sky, and pushed him to go meet them.

So Niu Lang travelled to the lake, and at the ox’s encouragement, hid the robes of one of the sisters. When this last sister, Zhi Nü emerged from the water, she searched and searched for her robes, but could not find them, growing clearly more flustered. Embarrassed, Niu Lang emerged from the bushes with her clothes, and admitted to Zhi Nü what he had done. He begged her forgiveness and the chance to talk with her, perhaps to show her more of his humble world.

After her initial shock, Zhi Nü found herself excited by this offer to spend more time on Earth, as well as intrigued by this sincere human. So the two journeyed together across lake and mountain, exploring earth’s wonders, seeing it anew through each other’s eyes. As so often happens, soon they were deeply in love.

They were married in a simple wedding with townspeople as witnesses, and with her weaving and his hard work they made a home together. They had two beautiful children, and, the myth says, their love for each other and their family flourished.

What the myth doesn’t say, but which I wonder: did they know it couldn’t last, this marriage of a divine being and mortal man? Did they know deep down that separation eventually would come for them too? Or did they hope - was it fooling themselves? - that their time together wouldn’t end?

The Jade Emperor strictly forbade marriage to mortals – an unacceptable breach of the divide between the heavenly and mortal realms – so when he learned of this union, he was furious. He waited for Zhi Nü’s return to her duties, but when she did not come he sent her mother and a host of troops to return her to the skies.

What could Zhi Nü and Niu Lang do? Their parting was bitter, their farewell like arrows to the heart.

Later that night, as Niu Lang wept, he remembered the passing of his old ox friend, and the magical properties of the hide. Taking their children in his arms, he wrapped himself in the hide and soared to the heavens in pursuit of Zhi Nü. But the Jade Emperor and queen mother anticipated this chase, and caused a rushing river of stars to cut off Niu Lang’s path. Niu Lang was forced back. There was no way to match this raging current: all he could do was reach for the distant crying figure of Zhi Nü, their tears but drops in the frothy rage.

This is the scene we see in the summer sky, Niu Lang, as Altair, with his two children flanking him, far across the Milky Way from Zhi Nü – Vega. As I watch them now I wonder why the creator gods tolerate such separation, indeed, even enforce it? Why? why?? why??? Why can’t the mortal and the divine meet in the depths of the starry night?

I know, somewhere deep inside, that nature cries out at this separation. And indeed, in the legend, Nature responds. The happy magpies, those bearers of good fortune, are said to have heard the weeping. On the seventh day of the seventh lunar month, the magpies (represented by Deneb and its surrounding bright stars) swept down that river of Milky Way. They gathered together to form a feathered bridge that the lovers might cross, and be, for a day, united.

The Jade emperor and queen permit this meeting, which is, perhaps, a small sign of divine mercy. But it is short lived. After a single day together, Niu Lang and the children are forced to return over the bridge, and I wonder at their courage as they take that step. As the Song dynasty poet Qin Guan so aptly put it, “how can one have the heart”?

And yet, we still imagine this reunion. How dreamlike the touch that they’ve so long longed for. The loudness of the thumping of their hearts. And in their tears of joy, the touch of the bittersweet that their time is so short. Oh the desire to make the hours count.

And they must count. The legend declares that the love of this family continues, even over the distance of space and time, divinity and mortality.

Tonight, as I watch, it’s partly cloudy, Vega coming in and out of sight. So fair, so distant. I think about how Vega for decades served as the astronomical calibration star: all star brightnesses and colors were measured relative to Vega: it was, by definition, perfectly white.

And I wonder how many others have wished upon this pristine star. It winks at me between the clouds. I make my wish. And wonder: what would we too do, for love?

Hi Luke, Aunt Padyll here. That is an absolutely beautiful story. Thank you for sharing it. Just an FYI, I have looms and used to be a handweaver in my younger years. I really enjoy your writing and hope you are well.

Hey, Luke!

Cool story as always.

When you write about constellations, I find myself wanting pictures of these stars with Chicago landmarks as references.

Do you know anyone that posts pictures like that?