Author’s note: Preparing for this essay on total solar eclipses for Christianity Today I found I had lots of additional information and thoughts which didn’t fit in that essay. Plus, who wouldn’t want advice from an astronomer? So for today’s post I’ve gathered together a few of my writing crumbs, and a bit of friendly advice. I hope you enjoy!

The early afternoon of April 8 most of North America will experience some sort of solar eclipse. You want to know about this. You want to be the most pumped of your friends about this. You want to impress everyone with your knowledge, passion and joy about the biggest astronomical event of the decade.

To that end, here’s a way too long information dump of 18 things to know. You’re welcome – it for sure will make you the coolest kid at the party!

A solar eclipse is when the moon casts a shadow on earth, blocking some or all of the sun’s light from our point of view. This is in contrast with a lunar eclipse, when the earth casts a shadow on the moon.

Figure 1: Standard diagram demonstrating Solar and Lunar Eclipses. From Encyclopedia Britannica. Most people in North America will experience a partial solar eclipse, where only part of the sun’s light disappears. Partial solar eclipses are interesting: if you pay careful attention you may notice a changing of the light. In Chicago, for example, the light will start to feel eerie, the feeling you get before a tornado filled storm, when things are just a little too yellow. Light patches under trees will take on crescent shapes, shadows will have a sharper edge.

Figure 2: A narrow path of earth experiences a total eclipse here the moon completely blocks the sun from Earth’s perspective. A much wider area experiences a partial eclipse. Figure from Sky & Telescope. Some lucky people along an approximately 100 mile wide path from Mazaltan, Mexico to Dallas, Texas to Indianapolis, IN, to Buffalo, NY will experience a total solar eclipse (see an interactive map here). If you are at all within traveling distance, it’s 1000% worth it to make the effort to go see it. “Seeing a partial eclipse bears the same relation to seeing a total eclipse as kissing a man does to marrying him, or as flying in an airplane does to falling out of an airplane,” Annie Dillard writes in her excellent essay Total Eclipse which you should drop everything now and read (especially if you would like a sliver of understanding of total eclipses). “Although the one experience precedes the other, it in no way prepares you for it… What you see in a total eclipse is entirely different from what you know.”

If you are traveling, do watch the weather. You won’t see a lot through thick clouds. Trying to find enough cell service in the Smoky Mountains to find up to date weather was one of the most stressful parts of my first total solar eclipse viewing in 2017. Also, be aware, traffic may be a nightmare. Many places in the path of totality have declared a state of emergency, expecting their populations to double, triple, or more during the eclipse. You may want to go early and stay late if you can.

The economic impact of the eclipse is expected to be huge. Over half the US population lives within 250 miles of the path of totality (see very interesting visitor estimates here). An economist in Texas expects it to be “the most profitable 22 minutes in Texas history.” In Bloomington, IN singer, songwriter, and actress Janelle Monáe will perform in the football stadium and William Shatner (think Captain Kirk) and Mae Jemison (the first woman of color to travel in space) will speak. NASA is broadcasting live from the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. This thing is huge. (Note: if you can’t make it to totality, do watch the NASA broadcast!)

This should have been #1, but except for the few minutes when the sun is completely blocked during a total eclipse, NEVER LOOK DIRECTLY AT THE SUN, even if it’s 99% covered! Humans can’t handle the light: even a couple seconds can yield permanent eye damage, and you won’t even feel it happening. The only safe way to view the sun is through approved solar eclipse glasses that block 99.99% of the light (there’s a list of approved vendors on the AAS website. Get them now, they are going fast, and the eclipse is nigh!), or through a projection through a pinhole, which effectively does the same (here’s a document with some examples and instructions I put together, borrowing heavily from other sources online).

Pinhole images, or “camera obscura” are really interesting, and are something you can make in 5 minutes with scissors, a nail, tape, and stuff from your recycling bin. The principle is this: a very small hole only allows specific light rays through. So rather than getting just blurry light on the other side, you can actually get an image of the object emitting the light. Do try this at home:

Poke a nail hole in a paper plate or equivalent.

Hold the paper plate maybe 2 feet away from a white wall or screen, and shine a very bright light through the hole. I advice making cardboard cutouts to change the “shape” of the bright light - for example, I taped a piece of cardboard with a person shape cutout to my bright light.

Here’s the crazy thing: the image you’ll see is not the circle of the hole you poked but the image of the light — of the person cutout — flipped upside down. It’s an amazing phenomenon. With only a tiny prick of light, it turns out you can see more; you have to block the light to really see. It flips my thinking on its head.

Bonus: if you really want to make your head flip, take a piece of glass (e.g., out of a picture frame), and stick some small face beads or other tiny dots on it to cast shadows. Then shine the person shaped light on them. You’ll see person shaped shadows on the wall. It’s crazy. You can’t make this stuff up.

There seems to be some confusion in the articles I read about how common solar eclipses are. While it’s true that there’s the potential for an eclipse every 6 months, and partial solar eclipses are reasonably common, on average a total solar eclipse occurs somewhere on the planet every 18 months, and for a given location, they occur, on average, more like every 400 years. The next total solar eclipse in the continental US is in 2044, and that basically only in Montana and North Dakota. So while not unheard of, they are pretty rare.

Of course, on cosmic timescales even every 400 years is pretty frequent. A sort rapid blinking, a wetting, a cleaning of the eye. Interestingly, the moon is very slowly moving away from earth, so that it slowly appears smaller and smaller. The sun is also very slowly getting a little bit bigger. The net effect is that in a few hundred million year the moon will not appear big enough to fully block the sun, and solar eclipses will be no more.

You may have heard of annular eclipses. Annular eclipses are just a special kind of partial eclipse. Sometimes the moon is a little farther from earth (or the earth a little closer to the sun), so the moon appears smaller in the sky than the sun. If it passes in front, it won’t block the whole thing. You’ll see a ring of sun surface around the moon, which is very interesting, but not falling out of an airplane.

I’m sorry that eclipses are not the regular, simple occurrences it seems like they should be. The moon orbits the earth, the earth orbits the sun, they should line up fairly regularly, right? Well, the problem is, the orbits are a bit of a mess. For one, the moon’s orbit is tilted 5.1 degrees relative to earth’s, which means that most of the time its shadow would fall above or below our planet. But even the times that do line up are not particularly consistent. The sun tugs on the moon’s orbit, earth’s slight fatness tugs on the moon’s orbit. The moon and the earth don’t go in perfect circles, and don’t always go the same speed. So it’s a lot. Dedicated smart humans with computers can calculate them, but I’d rather not. It’s not straightforward or easy, once you start looking into it. Like a lot of things in (and out of) this world, come to think of it.

Drawings of eclipses like the ones in Figures 1 & 2 (or on NASA’s otherwise very helpful site) are not to scale. They are not even close. It’s very difficult to try to fit the scale of eclipses in our heads. Here’s one way to try. Imagine the earth is a regular marshmallow, slowly roasting on the end of my roasting stick. The moon would be about the size of small fly that just landed on my hand. The sun would be the size of a pop-up camper, and would be located several loops away - far enough that it appears the same size as the fly, from the marshmallow’s perspective. In principle, if you line up the camper and the fly and the marshmallow just right, the fly will cast a shadow on the marshmallow. That’s an eclipse. Savvy? (Ha!)

Then again, I’m not sure I want to actually try to fit it in my head.

The history of humans experiencing solar eclipses is very interesting. Stories include people dying of fright (take some of these with a large grain of salt), examining livers, and confirmation of Einstein’s mind bending view of gravity called general relativity. Some people respond with terror. Other’s with indifference. I just sit here in awe.

We adapt to light quicker than we adapt to the dark. Something about our eyes and evolution I don’t fully understand. Anyway, this puts a slant on our experience of a total solar eclipse: things seem to brighten quicker coming out of the dark. Which seems opposite of my experience. It seems so often we are plunged into dark, and emerge slowly, if at all. Shadows are sticky things.

So sticky, in fact, that each planet, each object orbiting the sun has one at all times. One of my favorite things about this, which I hope to highlight in the upcoming article, is that the shadows are what create our experience of night. It’s when we’ve spun into earth’s shadow that it’s nighttime, when we emerge the sun rises, from our perspective, and it’s day.

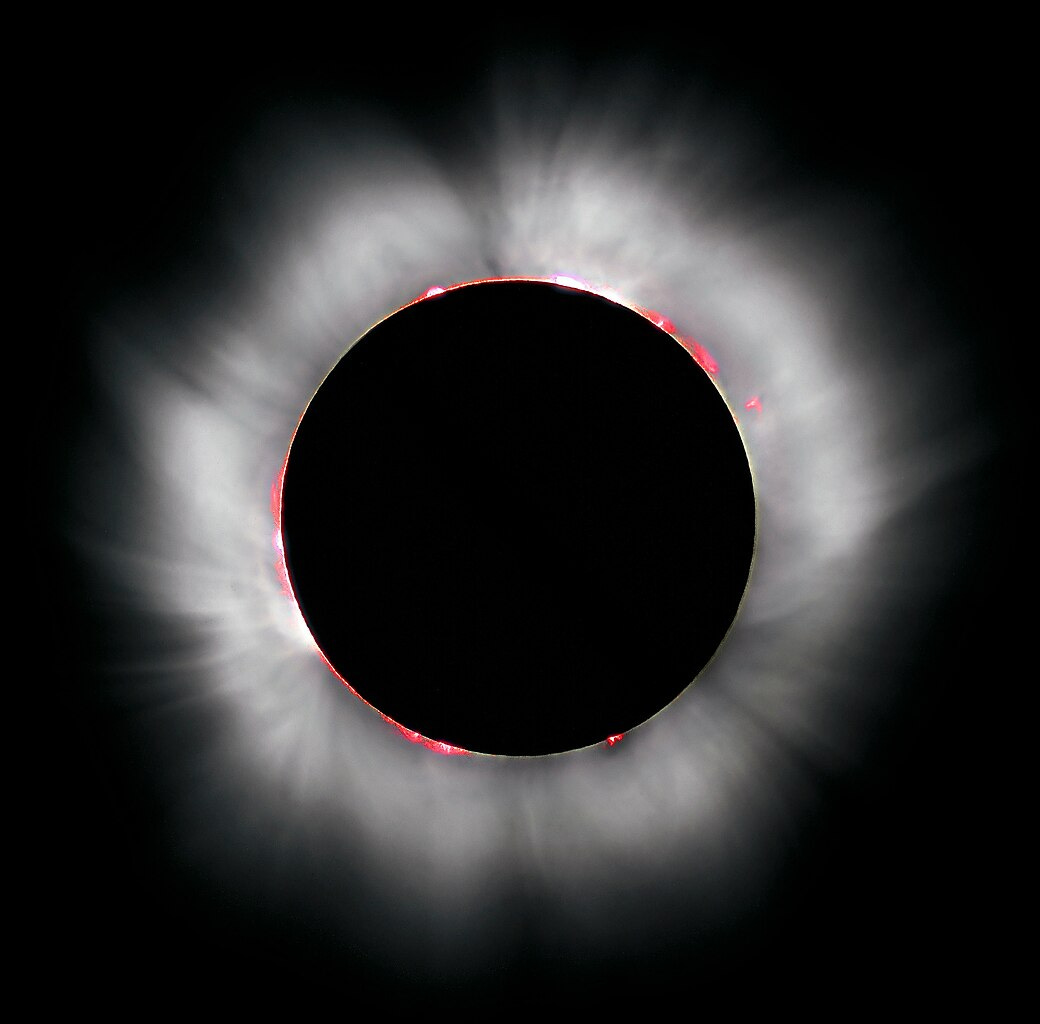

This means, interestingly, that when we are watching a solar eclipse, someone living on the moon looking at earth would be experiencing night. But not really as dark a night as it appears. At this moment of eclipse, when the moon appears blackest before our eyes, the night, from the moon’s perspective, is actually most full of light. It’s “full earth” phase for the moon, the earth reflecting the sun’s bright rays back on to the moon’s night side. Earthshine, we call it. In fact, if you find a deep exposure image of a total eclipse you can see craters on the moon, highlighted by earth’s reflected light.

Figure 3: Earthshine on the moon during a total solar eclipse. Credit: Chuck Claver, on Wikimedia commons. One final cool thing. The moon, during a solar eclipse, is in “new moon” phase. We only see its dark, unlit side. We only see its night. But this is the moment that we think of as a time of rebirth. The moon’s monthly cycle starts over again. From this darkness will come new light. Which is, perhaps, just semantics. But I find it a hopeful thought.

This only scratches the surface (like the tip of the moon’s shadow, ha!). Do (selectively) binge youtube about this. Do go to a watch party. Do take the day off work and get to the path of totality. Be blessed by this cosmic experience, a brief blink of the moon’s night!

My husband's family lives in the path of the totality, so we're using an almost-once-in-a-lifetime astronomical event as an excuse to visit them!

I've been keeping an eye on the moon all week, watching it get slimmer and slimmer, like a celestial hourglass with the grains slipping away. Each time I see it, I get excited to see the totality soon.

Thanks for the excellent article!